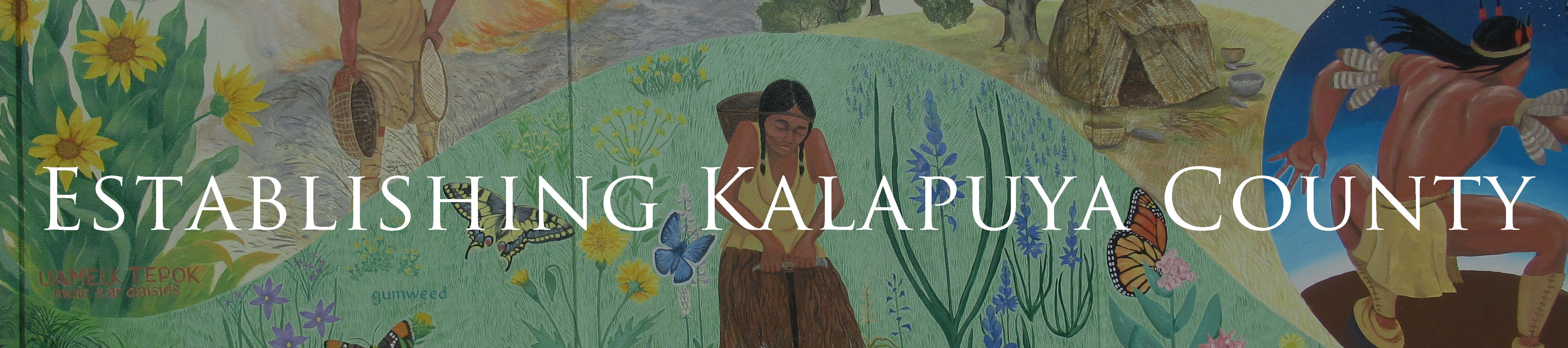

The "Establishing Kalapuya County" project begins with the goal to rename the county, but it involves much more than that. This is about reshaping the public view of this place to put it into an Indigenous context. We seek to connect our place and our people with the human past that predates Euro-American settlers and to welcome Native people firmly back into today’s society, along with their culture and traditions. Changing the county name is an important step in cultivating mutual respect and a supporting environment for all minorities in our community. Our name is a constant reminder of how we see ourselves.

QR Code Petition Flyer Donate to Our Fundraiser Project Flyer Downloadable Sign

This project was inspired by a petition from Esther Stutzman and Dr. David Lewis, both Kalapuya descendants, to the Lane County Board of Commissioners on June 25, 2020, requesting the name change. Our Executive Director, Dr. Richard Pettigrew, submitted an opinion piece to our local newspaper, The Register-Guard, titled “Time to Honor the Kalapuya,” published June 30, 2020. Many community members sent us support messages after Dr. Pettigrew's letter appeared in the newspaper. The COVID pandemic then held back any further action for two years. Now, however, spurred by a new grant opportunity through the Gannett Foundation and The Register-Guard, we have gotten back on track. Benefiting from two years of quiet consideration, we’ve developed a broader view of what needs to be done.

Dr. Pettigrew more recently submitted another opinion piece to The Register-Guard, titled "Support Project to Rebrand Ourselves Kalapuya County" published July 31, 2022.

On September 23, 2022, the City Club of Eugene held a public forum called "Renaming Lane County," with presentations by Dr. Pettigrew (in absentia, as he was ill, but Mary Leighton delivered his text) along with drs. Douglas Card and David Lewis. This program is described on the City Club website, which includes a link to a YouTube video recording of the program. The audio of the program is available on KLCC on their City Club of Eugene program page.

Other actions envisioned by the project include:

- Organizing a corps of volunteers to assist with the work

- Investigating actions needed to rename the county, which will include approval by the electorate for a change to the county charter.

- Exploring ramifications and consequences of renaming the county (e.g., what about Lane Community College?)

- Securing legal and lobbying help to bring about the name change

- Compiling Kalapuya place names, putting them on the map, and using them publicly

- Exploring options for changing some place names to their original Kalapuya place names (such as “Champ-a-te” for Spencer Butte and “Ya-po-ah” for Skinner Butte)

- Employing the Kalapuya vocabulary as much as possible in statements, publicity and documents

- Encouraging schools and teachers to include Kalapuya culture in their curricula

- Creating and distributing documents about Kalapuya history, culture, lifeways, and prehistory for the public

- Promoting the commissioning of a statue in Eugene honoring our Kalapuya forbears.

Why should we do this?

Many people here feel that the namesake for the county, Joseph Lane, is not an appropriate person to memorialize, as his history in key ways runs counter to our vision of ourselves.

We feel that replacing County name is not only necessary and fitting, but also an opportunity to right a serious wrong in our history. The Native American people of the southern Willamette Valley were various bands of the Kalapuya, whose ancestors arrived here many thousands of years ago and managed this land in a responsible way for many hundreds of generations. Decimated by disease in the 1830s, only a remnant of these people were here to meet the Euro-American settlers when they arrived in the late 1840s. The settlement of the land by white Americans from the East caused broad starvation and poverty among the tribes. Malaria by itself caused a 95% population decline, and so the remaining Kalapuyans were then subject to the whims of the newcomers. Although many have considered the Kalapuya to be extinct, their descendants are still among us and their legacy remains, albeit not nearly as visibly as it should be.

This project addresses the need for the community to be informed not only on the last 200 years of history, but also about the previous 15,000 years of human existence here. Renaming this place as Kalapuya County represents a purposeful shift in our historical narrative to include an emphasis on Kalapuya culture and history, and to create a more welcoming community for Native people and everyone else. Importantly, this is not really about rejecting a historical figure, who always will remain important in our story, but instead about creating a truthful context for making a better future for all of us. We call this project “Establishing Kalapuya County” because it is not limited to changing the name of the County, but instead involves an array of actions to make the name change the beginning point for a widening of public appreciation for our deeper and more inclusive history.

What happened to the Kalapuya?

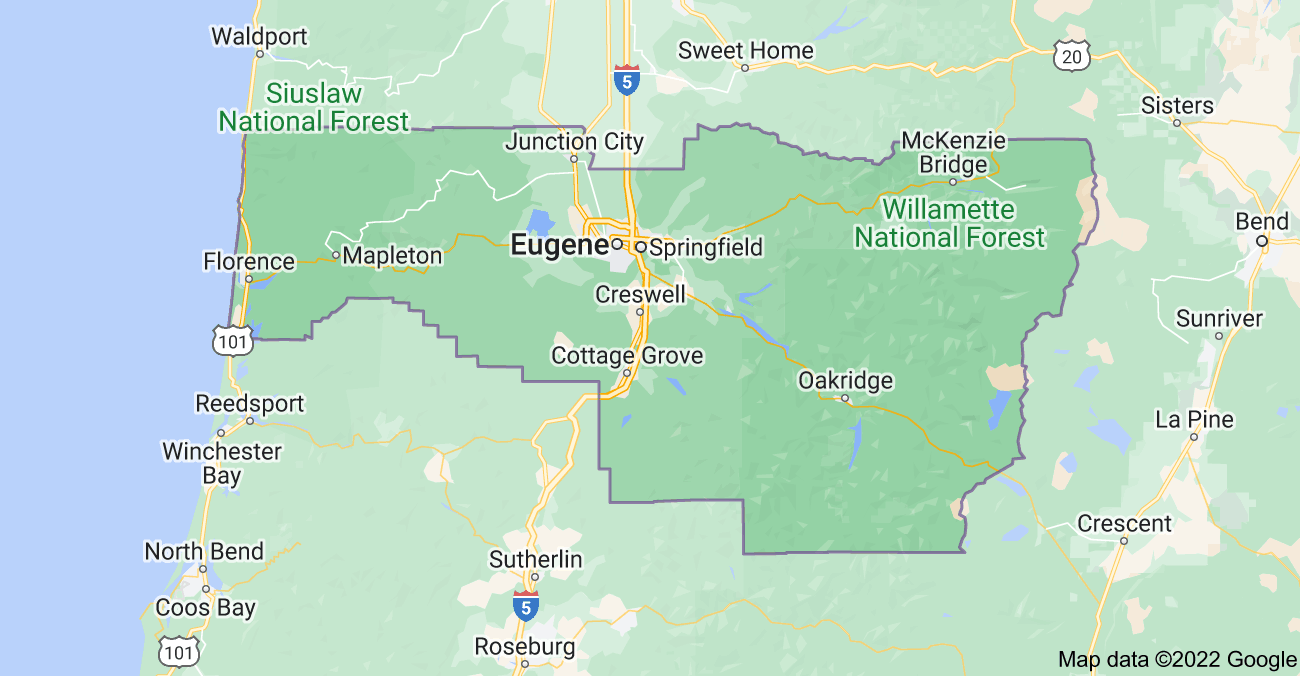

The Kalapuya are a Native American cultural and linguistic group whose original territory encompassed the Willamette Valley and areas southward to Yoncalla and the Umpqua River. Many Kalapuya descendants today are members of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, located in the Coast Range between Salem and Lincoln City. Others are descended from ancestors who refused to relocate to Grand Ronde when ordered to do so back in the 1850s.

The Kalapuya subsisted on the abundant natural resources of their land, focusing to a great extent on wetland plants such as camas, waterbirds such as duck and geese, herd animals such as deer and elk, and a huge variety of other plant and animal species. They managed the land intensively, employing fire to keep it open and productive. The Willamette Valley was not a wilderness, but a carefully and intensively maintained landscape. The Kalapuya were not migratory or nomadic, but quite settled, with each band living in and managing its own specific section of the Valley, harvesting plant and animal resources in an annual cycle that had been followed for thousands of years. (See our references below for more information on the Kalapuya and their lifeway.)

Population estimates vary and are based on very indirect information. Prior to the arrival of European and American ships along the Oregon coast in the late 1700s, a reasonable guess is that the Kalapuya comprised about 15,000 people. However, this number declined very quickly after contact, mostly due to disease. Even before most contact, a smallpox epidemic in about 1781 swept through the Pacific Northwest, no doubt including the Willamette Valley, and killed at least 30 percent of the population.

Lewis and Clark explored the lowermost reach of the Willamette River in 1806 during their cross-continent journey and made reference to the Willamette Valley and its people in their journals, based on interviews with people in the Portland area. A scouting party directed by Donald McKenzie of the Pacific Fur Company in 1812 are the first Euro-Americans known to have actually seen the Willamette Valley. They named the McKenzie River after their leader. Over the next two decades, Euro-American fur traders, mostly based at Ft. Vancouver (today’s Vancouver, Washington), made regular trips through the Valley Beginning in the 1820s, some of them settled in the northern Valley, near what became Oregon City, but their numbers were very small.

In 1830, a malaria epidemic broke out in the Portland area, likely introduced by an American ship that anchored in the Willamette River. This disease devastated the Native population of the Portland Basin and by 1831 made its way into the Willamette Valley. Estimates of the epidemic’s mortality range from 80 to 95 percent within a span of three years. By the late 1830s, the Kalapuya population is estimated to have declined to about 600. By the early 1840s, white settlers, mostly arriving via the Oregon Trail in wagon trains, outnumbered the Kalapuya and were already draining marshes and tilling the soil, destroying the staple food supply of the Native people. These events were a true calamity for the Kalapuya. A culture and lifeway that had endured for thousands of years effectively ended as a functioning system within a decade or less.

The physical removal of the Kalapuya from their traditional lands came about following the “Treaty with the Kalapuya, etc.” that was signed and proclaimed in 1855. Here is a description from Wikipedia:

This treaty, generally referred to as the Kalapuya Treaty after the overarching name of the natives in the area, gave almost all of the Willamette Valley to the United States. The natives secured promises in return of a reservation and long-term support from the United States government in the form of money, supplies, health care, and the promise of protection from further attacks by settlers. At the time the treaty was signed, only 400 Kalapuya natives remained, having been reduced by disease and conflict.

In 1855 and 1856, these remaining natives were forcibly resettled in what became the Grand Ronde Reservation, along with members of other native Oregonian groups. The reservation would continue to be served and recognized by the United States government until 1954, when the government terminated its trusteeship with the reservation. However, because the Kalapuya Treaty had been ratified by Congress and was therefore legally enforceable, it was used by the Kalapuya, now one of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, to regain federal support in 1983.

The promises of this treaty were not kept. The remaining Kalapuya people suffered mightily for a long time. In the words of Kalapuya descendants Esther Stutzman and David Lewis in their 2020 petition letter to the Lane County commissioners requesting that the county be renamed “Kalapuya County”:

The tribes had endured some 40 years of colonization, the effects of introduced diseases as well as the loss of their lands and so they knew that if they did not remove they would all die. The 30 or so remaining Kalapuyans of the southern Willamette Valley, once removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation they shared with 27 to 35 other tribes, were then subjected to near-prison-camp-conditions, where for 20 years they endured starvation, malnutrition, lack of land, and basic necessities, and this caused hundreds of early deaths. There was very inconsistent support from the federal government, despite promises by Indian agents that they would be better off after removal.

The name “Lane County” was coined four years before the Kalapuya Treaty. Just four years after the treaty, in 1859, Oregon became a state. Native American people, the first people of this land, were denied United States citizenship until June 2, 1924.

Who was Joseph Lane?

Few people in our county, after learning who Joseph Lane was and what he did, would want him to be our county’s namesake. He was appointed the first Governor of the Oregon Territory in 1849. Just two years later, in 1851, Lane County was formed and named after him. This was while he was a very active politician, but before the Democratic Party split on the issue of slavery. Lane favored any slaveholder’s right to bring slaves into any territory. He was openly pro-slavery and, when the issue came up, openly favored Confederate secession from the union.

When Oregon became a state in 1859, Lane was elected as one of Oregon’s first two United States senators. According to Wikipedia, “Lane became notorious for an exchange with Andrew Johnson of Tennessee on his last day in the Senate. Johnson had spoken in favor of the Union and denounced secession. A referendum on secession in Tennessee failed shortly thereafter, generally credited to Johnson's speech. On March 2, Lane accused Johnson of having ‘sold his birthright’ as a Southerner. Johnson responded by suggesting that Lane was a hypocrite for so accusing Johnson when Lane so staunchly supported a movement of active treason against the United States.”

In the 1860 United States presidential election, Lane was nominated for Vice President on the ticket of the pro-slavery Southern wing of the Democratic Party, as John C. Breckinridge's running mate. Their ticket came in second to the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln. While Joseph Lane did not actively participate in the Civil War, his son John left West Point and accepted a commission in the Confederate Army. Although the Oregon electorate was overwhelmingly racist, the majority opposed slavery. Lane's pro-slavery views and sympathy for the Confederate States of America in the Civil War effectively ended his political career in Oregon, about ten years after his name had become attached to this county.

Many people agree that the connection between the name “Lane County” and Joseph Lane is sufficient to justify renaming the County. Our proposal is to rebrand this place as Kalapuya County, emphasizing a more accurate and inclusive historical narrative and making it clear that we stand for equal rights and equal justice for all groups of people, expressly including the first people of this land.

Feel free to peruse the following references to learn more about Joseph Lane:

How Oregon named a county after a Confederate sympathizer (Oregon Public Broadcasting)

Joseph Lane (1801-1881) (Oregon Encyclopedia)

'A lot of people who take a look at the history of Joseph Lane don't like what they see'(KMTR)

Oregonian almost became President; luckily, he didn’t (Offbeat Oregon History)

The racist history of Lane County’s namesake, Joseph Lane (Daily Emerald)

FAQs

Q: Did Joseph Lane have a slave?

A: This subject is debated. It’s not certain that Lane had a slave, although he did have a ward that many have suggested was actually a slave.

Q: Did the Kalapuya keep slaves?

A: Yes. Slavery existed among tribes throughout the Northwest, as is true also for Europeans and Americans well into the 19th century.

Q: Are you rejecting Joseph Lane as the County namesake because he kept slaves?

A: No. We don’t know for a fact that he had a slave. However, he was a Confederate sympathizer and supported the institution of slavery in America at a time when it was highly controversial and became a focal point of the Civil War. Our focus is to have a County name that we can be proud of, rather than one we have to make excuses for.

Q: Have the Kalapuya people been here for thousands of years?

A: The name “Kalapuya” is the name we give to a group of people based on their language and culture. They actually had other names for themselves. Based on linguistic and archaeological evidence, the Kalapuya and their ancestors have been here for many thousands of years. Over that time, their language and culture evolved, as is normal for any group of people, including English-speakers.

Q: Would it be expensive to change the name of the County, given all the signs, uniforms, vehicles, letterhead, business cards, and so forth that would need to be changed? Would it cost millions?

A: Without doubt, money would need to be spent to make these changes. So far the County has not made an assessment of how much it would cost. It’s not clear it would cost millions.

Q: What actions could be taken to mitigate the expense of changing the County name?

A: Possibilities exist to limit the financial impact of the name change. Here are some options:

1. Phase in the sign and label replacements over time rather than doing it all at once. The process of making those changes could be a positive promotional tool for the County.

2. Find outside funding sources to help defray the costs, such as grants or contributions. With some positive promotion, this should be quite possible.

Q: If, as is likely, most people here don’t even know who the County’s namesake is, why does it matter at all whether we change the name?

A: No matter how many people know who Joseph Lane was or what he did, the fact is that he is the namesake for the County. Besides that, when the County name is changed, that name will actually be meaningful to people, a positive meaning that instills pride in community about where we live and what we accomplished. We will have replaced a name that is meaningless or has negative associations with a name that clearly identifies this place and has positive connotations.

Q: Is the timing of this project related at all to the upcoming November election and a fear that the “liberal bloc” will lose it’s majority? After all, if the County commissioners don’t vote to put this matter on the ballot, it would require an expensive signature petition campaign to put it on the ballot.

A: No considerations of that kind played a role in our decision to launch this project. Our Executive Director, Rick Pettigrew, proposed the name change in a Register-Guard op-ed back in June 2020, but organizing to accomplish it was held back for two years by the pandemic. We were in part spurred by the recent appearance of a grant funding opportunity promoted by The Register-Guard and their owner, Gannett, which we hope will help bring this project to a successful outcome. We hope to avoid any linkage of this effort to the political divisions that currently plague our country. We are not a political organization, and we don’t see this as a “liberal” or “conservative” issue.

Q: Could this project bring economic benefits to our area?

A: Very much so. Changing the County name and promoting a more inclusive historical narrative will bring attention to this place from around the country and the world. Many people and companies will develop a more favorable impression of Kalapuya County and reflect that by coming here and investing in our community.

Q: Wouldn’t it be simpler and less expensive to simply change the namesake of the county to a different person named Lane, such as Harry Lane, the grandson of Joseph Lane?

A: While this workaround would be simpler and less expensive, it would not change the unavoidable fact that the county was named originally for Joseph Lane, nor would it meet the goal to acknowledge the original people of this land. It would not generate a more inclusive historical narrative or serve to expand public awareness of our deeper history. We would be selecting a namesake purely because his name was Lane, not because he was someone who has inspired us. It would not be a true rebranding of the county, it would not remind us and future generataions of our diverse origins, and it would have the appearance of papering-over an embarrassing historical fact. We feel that it is time to move our self-perception in a more positive direction.

Kalapuya People in Our History

Eliza Young, Indian Eliza (c. 1820-1923) (from “Travels, Campmeetings, and Off-Rez Settlements of the Western Oregon Tribes” by Dr. David G. Lewis; QUARTUX: Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology, August 14, 2016; accessed at https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/2016/08/14/travels-campmeetings-and-off-rez-settlements-of-the-western-oregon-tribes/)

Eliza Young was born in the Mohawk Valley, the Land of her father of either the Pee-yu or Calapooia Kalapuya Indians. Her mother was from the McKenzie River, the homelands of the Winfelly Kalapuya. In the 1830s, her parents died, like the many Kalapuya of this period, likely of introduced diseases in the valley which caused the deaths of some 97% of the tribes in the Willamette Valley. Jacob Spores, an early settler to the area, took Eliza in and raised her in the Coburg area.

Later Eliza moved to the town of Calapooia, now renamed Brownsville, and became the 3rd wife of a Pe-u (Mohawk) Kalapuya Indian. They were removed to the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation in 1856 with some 27 other tribes. Eliza left her husband many times because of his brutal treatment of her and met Indian Jim (Jim Young). Indian Jim purchased Eliza from her husband for 15 ponies, a rifle and 15 dollars. They moved to the Calapooia River near Brownsville, built a house and had two children, both of whom died at an early age. Indian Jim treated Eliza badly when he drank and eventually ended up in prison. They continued to be attached to each other for many years despite Jim’s drinking.

Eliza harvested traditional berries and materials for weaving throughout her life. She would sell the berries and woven baskets to the people in Brownsville to make a living. Eliza would also take on odd jobs and housework from the neighboring settlers. Local stories of Eliza state that she was neat and clean and was extremely intelligent. Later in her life she went blind and yet continued to harvest weaving materials and making baskets on the porch of her house (shown). Her specialty was purses. A local Brownsville family hosted her on their farm and she lived to be over 100 years old.

At her death in 1923 in Brownsville, the local papers stated that she was the “Last of the Calapooyas.” This was of course incorrect as most of the Kalapuya Indians removed to the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation and their descendants remain members there today. Eliza was one of the last of the Kalapuyans to live off of the reservation in her original homeland during the time when it was illegal for Indians to be off of a reservation. Eliza’s baskets are now collected in museums and private collections throughout western Oregon.

Eliza Young

Eliza Young

Chief Halo (from “Travels, Campmeetings, and Off-Rez Settlements of the Western Oregon Tribes” by Dr. David G. Lewis; QUARTUX: Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology, August 14, 2016; accessed at https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/2016/08/14/travels-campmeetings-and-off-rez-settlements-of-the-western-oregon-tribes/)

Chief Halo (Halo Tish) commonly shortened to Chief Halo (meaning “having little” or “needing little”), was leader of the Yoncalla Kalapuya Tribe and was married to Du-Ni-Wi, one of several wives. He remained on the Applegate family donation land claim in the Umpqua Valley after removal of other tribes to reservations. Halo and his family were prominent Native people in the community of Yoncalla and for generations were friends with the Applegate family.

The Yoncalla chiefs signed the Treaty with the Umpqua and Kalapuya with the U.S. government on November 29, 1854, and the tribes removed to the temporary Umpqua Reservation, west of Roseburg. In January 1856, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer began removal proceedings to the permanent Grand Ronde Reservation. Jesse Applegate wrote that Halo refused to go to the reservation, saying

“I will not go to a strange land.” This was not reported to the agent. When the tribe arrived on the reservation without the chief the agent was troubled, and came to our house to get father to go with him to visit the chief. We boys went with them. When Halo saw us coming he came out of his house and stood with his back against a large oak tree which grew near the door. We approached in our usual friendly fashion, but the chief was sullen and silent. He had lost faith in the white man. The agent said, “Tell the old Indian he must go to the reservation with the other people, that I have come for him.” The chief understood and answered defiantly, “Wake Nika Klatawa,” that is ,” I will not go.” The agent drew his revolver and pointed it at the Indian when the chief bared his breast, crying in his own tongue as he did so, “Shoot! It is good I die here and am buried here. Halo is not a coward, I will not go.” “Shall I shoot him?” said the agent. “No!” cried father, his voice hoarse with indignation. The chief standing with his back against the giant oak, had defied the United States. We returned home leaving the brave man in peace. Father and my uncles protected the old chieftain and his family and they were allowed to remain in their old home. (Applegate Recollections of a Boyhood)

Halo and his family remained in Yoncalla, where the Applegates built a house for them.

Halo had a Native name, Cam-a-phee-ma, which in Yoncalla Kalapuya means “fern,” which became the Fearn surname for the family. Chief Halo and his sons, Mack, Jake, and Sam (Be-el)— finally decided to live for a short time on the Grand Ronde Reservation. By 1891 they had returned to the Umpqua Valley, where they received off-reservation allotments.

In the 1860s, Chief Halo went into business with a local settler, John Walker, who would found the town of Walker. They built a fish trap on the Row River, four miles east of Cottage Grove, where they alternated days to clear the trap of salmon, trout, and eels. Chief Halo remained active until his death in 1892. He is estimated have been at least seventy years years old.

“While living on Row River, he went into business with Halo Tish. They constructed a crude trap on Row River. Mr. Walker took the catch one day, Halo Tish the next. If Mr. Walker was too busy to go to the trap on his day, Halo Tish brought his fish to him.” (Alice M. Fox, Community of Walker)

Chief Halo

Chief Halo

Cottage Grove Kalapuyans (from “Travels, Campmeetings, and Off-Rez Settlements of the Western Oregon Tribes” by Dr. David G. Lewis; QUARTUX: Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology, August 14, 2016; accessed at https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/2016/08/14/travels-campmeetings-and-off-rez-settlements-of-the-western-oregon-tribes/)

“Several hundred Calapooya Indians lived within the area of present day Cottage Grove. Many small villages were located along the banks of the Coast Fork of the Willamette River and its tributaries. In addition to the Calapooyas, the Klamath Indians from Eastern Oregon often crossed the mountains to fish the Row River. They made their camp in the area of present Wildwood Park. The Klamath fished with spears and dip-nets to catch the fish that collected in the pool at the base of the falls. The fish were then dried and put into large baskets to be taken back over the mountains.” (Gene Savage, Looking Back, Dec. 18 1991)

Cottage Grove was a known gathering location. In the summers, the local tribes would leave the reservations to travel about the Willamette Valley and take jobs harvesting the crops. The Indians who gain special travel letters and get signed out in the Passbook to allow them to travel off-reservation. Indian without the travel permission would be subject to being detained by law enforcement. The Indian agent would then get a note asking them to come get the Indians from the jail.

During these outings the tribes would have gatherings in specific locations. These places were called council grounds, or meeting grounds, or council trees. There was normally a large field where the tribes had been using the location for a long time. Pleasant Hill had such a location and Polk Scott, one of the last Native shaman at the Grand Ronde reservation, was the leader of the group there. Another gathering location was at the Cottage Grove fair grounds. the city has a heritage fair there every here even today. The Salem Fairgrounds site mentioned above was also probably a traditional gathering location. Most large tribal areas had sites to hold meetings, sometimes called campmeetings.

“The Calapooya Indians adapted to the White Man’s ways very quickly. They soon were wearing the same clothing as the settlers. They learned and spoke the language of the whites. Indian and white children often played together and attended the same schools. Inevitably, the ever increasing numbers of white settlers caused the Indians to lose their lands. In Curry County, the Calapooya were removed to reservations.” (Gene Savage, Looking Back, Dec. 18 1991)

“A favorite local living place of the Calapooya was in the area of the Western Exposition Fairgrounds. The ground in the area had a hollow sound and the Indians believed that the Great Spirit spoke to them from the ground. Indian and white children alike enjoyed the sound of the ground as they raced their horses across the area.” (Gene Savage, Looking Back, Dec. 18 1991)

“As late as 1871 there were small isolated tribes of Indians living near Oakridge and Cottage Grove. The two groups were related and often visited back and forth. During these visits, the Indians near Oakridge took all their ponies and dogs to the settlement near Cottage Grove. The Cottage Grove Indian returned the visit, and at these times the population of the Indians settlements would swell to almost 100. It was unlawful for the Indians to homestead land. a man by the name of Black changed the names of the Indians and after considerable difficulty two Indians, Charley Tufti and James Chuck Chuck, succeeded in homesteading and securing title to two parcels of land containing 80 acres each. This was the maximum acreage permitted under the Homestead law at the time.” (Fred Macfarland)

“As late as 1910 there was a well established campground used by the Indians. The Indians of 1910 traveled by wagons and saddle stock… They hunted in the Calapooya Mountains.” (Fred Macfarland)

“The Indians came in large numbers to Lowell to pick hops in the hop yards there. they would return across the summit with salmon, dried fruits, and some green fruits and clothing; pick huckleberries and hunt in the vicinity of Rigdon and cross the Willamette Pass just prior to the snow storms in the early fall.” (Fred Macfarland)

Pleasant Hill Kalapuyans (from “Travels, Campmeetings, and Off-Rez Settlements of the Western Oregon Tribes” by Dr. David G. Lewis; QUARTUX: Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology, August 14, 2016; accessed at https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/2016/08/14/travels-campmeetings-and-off-rez-settlements-of-the-western-oregon-tribes/)

Chief Fisherman Bristow was the grandfather of Indian Sam Fisherman, and father of Jack Fisherman, Kalapuya Indians of the Pleasant Hill area. This is the area of the Winfelly Kalapuyan Indians who were likely related to the Yoncalla Indians, according to this story.

“Chief Fisherman Bristow was a treacherous troublesome character here during the fifties and early sixties (1850s-1860s). This surely old chief was given the name of Bristow, after that grand old Pioneer Elijah Bristow, who settled Pleasant Hill, in 1846, and who exerted a powerful influence over this wily old brave who was chief of the Pleasant Hill tribe of Calapooias.” … in 1878, there was quite a flourishing Indian Village just back of the McFarland Hill north of Town, among the most noted Indians being Jack, Polk Scott, Jerry and Bob, Indian Sam (Fisherman)… Enoch (Fearn) the sole survivor of the tribe. (Leader May 8 1903)

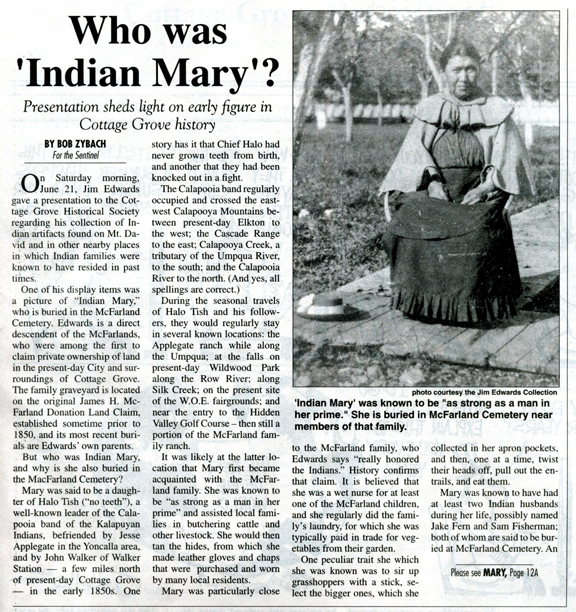

Indian Mary (from Cottage Grove Sentinel, June 25, 2014)

References and Links

Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s, by Robert Boyd (Oregon Encyclodpedia)

Kalapuya: Native Americans of the Willamette Valley, Oregon (Lane Community College Library, accessed at https://libraryguides.lanecc.edu/kalapuya)

QUARTUX: Journal of Critical Indigenous Anthropology | Davud G. Lewis, Ph.D.

https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/

Treaty with the Kalapuya, etc. (Wikipedia)